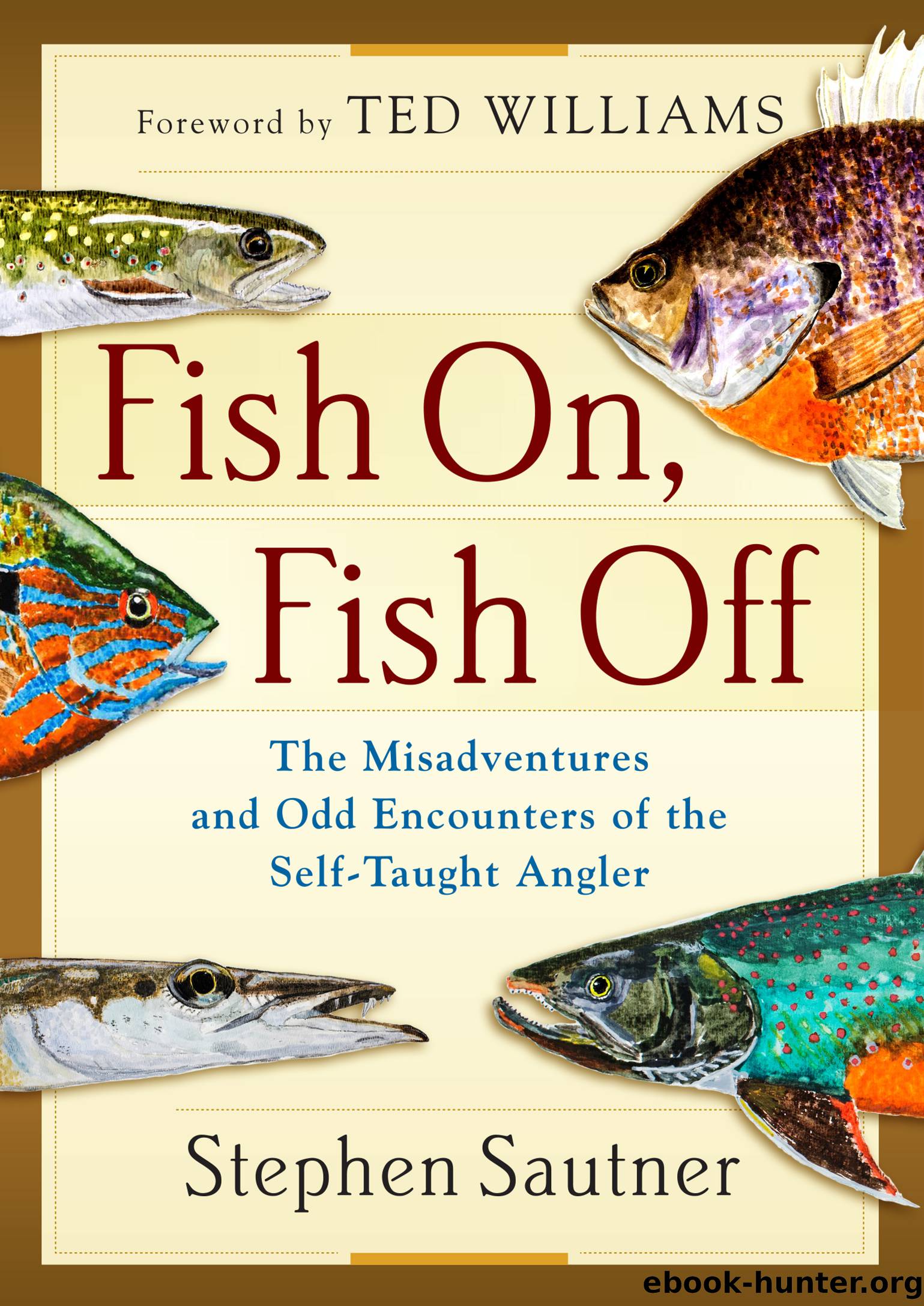

Fish On, Fish Off by Sautner Stephen;

Author:Sautner, Stephen; [Sautner, Stephen]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Lyons Press

Published: 2016-08-15T00:00:00+00:00

Night of the Living Hellgrammites

One of the best ways to learn the inner workings of a trout stream is to get a small minnow seine or a decent-sized aquarium net and wade into a shallow riffle. Have someone hold the net immediately down-currentâjust make sure itâs touching the stream bottom. Then start turning over rocks. Do this for a minute or two then lift the net from the water. If the stream is moderately healthy, you will now be staring at a seething mass of trout food.

Start picking through your haul to see exactly whatâs in there. Assuming youâve placed your net in a bona fide coldwater trout stream, itâs a safe bet that mayfly nymphs of various sizes will be crawling about. Some are mere fractions of an inchâmaybe blue-winged olives or this yearâs first molt of Hendricksons. Others are much larger, mottled, and flatâprobably March Brown or Cahill nymphs, a sure sign that the stream runs cold and clean year-round. Maroon-colored Isonychia nymphs will flip around like miniature shrimp. Place them in a bucket with some water and they zoom about like little submarines.

Clusters of small twigs and pebbles seemingly glued together may turn out to be the homes of stick caddisâlook for a hole in one end and you might see a small head staring back at you. Put them in the bucket with the Isonychias and they will eventually start lumbering along the bottom carrying their home on their backs. What might look like craggy, waterlogged beetles stuck in the net are actually dragonfly nymphsâugly creatures that belie one of natureâs most graceful fliers.

Virtually all of these critters are harmless. Even a two-inch stonefly nymph with an abdomen striped like a hornet will merely wander over your fingers fruitlessly looking for a rock to hide under.

But if you find something much larger in the net that looks like it belongs not on a trout stream but in a science fiction movieâthe one where the creature-from-another-planet crawls into your ear and eats your brainâyou have caught a hellgrammite. They can be as long as your index finger with a meaty, muscular body flanked on each side with wriggling centipede legs. The head is topped with a pair of hooked pinchers that can and will draw blood. They eventually hatch into massive dobsonfliesâ747-sized bugs that can easily be mistaken for bats when they buzz around trout streams at dusk.

Even their nameâHELL-GRAM-MITEâsounds scary, almost like some sort of medieval torture device: âNever mind the iron maiden; place the knave in the hellgrammite.â

And if regional nicknames are any indication of temperament, draw your own conclusion from hellgrammites, which, according to a favorite fishing book from the 1930s, are also called corruption bugs, crock hell devils, alligators, dragons, snake doctors, hell divers, flip devils, and water grampus. The last nickname is a bastardization of krampus, a European mythological monster known to haunt misbehaving children.

Except this is no mythological monster; these things are real. And as a group of us learned one late spring night on our annual camping trip on the Upper Delaware River, they will attack.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Fisheries & Aquaculture | Forests & Forestry |

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4128)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(3762)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(3527)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3238)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid(3197)

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything by David Christian(3145)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(2961)

How to Read Water: Clues and Patterns from Puddles to the Sea (Natural Navigation) by Tristan Gooley(2876)

Hedgerow by John Wright(2782)

The Inner Life of Animals by Peter Wohlleben(2776)

Origin Story by David Christian(2692)

How to Read Nature by Tristan Gooley(2669)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(2667)

How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell(2651)

Water by Ian Miller(2597)

A Forest Journey by John Perlin(2588)

The Plant Messiah by Carlos Magdalena(2458)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2367)

Forests: A Very Short Introduction by Jaboury Ghazoul(2337)